Meeting Samson Again for the First Time

If the story of the fighting Nazarite were a piece of architecture, it would be the Tower of London: a place to take the kids and wow with them with the gore-creating weaponry on a school holiday. Not somewhere to pop into before going to work, and definitely no sanctuary to retire to in the evening.

It's our loss. Samson is the Beowulf of Judeo-Christianity. Not simply because both narratives concern the adventures of a warrior who is finally beaten by a force greater than any man, but because so much of the language of the Bible and the archetypes found in its holy stories spring from these three short chapters.

If we don't regularly return to the story of Samson we can't spot the allusions to it in the rest of the Bible, or even claim to have an accurate understanding of the tale's key events and messages. In fact, the version of the story that most well-churched Christians remember is as likely to come from Jeremy Hypezeigger's Colourful Tales for Growing Kids than from a translation of the original text.

If you do return to Samson, prepare to be shocked when some of your most fondly remembered moments are found to be absent. Samson doesn't tell the boy who leads him up to the pillars to run for his life. No, the evidence suggests that he's flattened in the destruction which follows.

(An aside: Why is Samson known as the most successful newspaper humourist in the Bible? They gave him two columns and he brought the house down.)

But there's fascinating detail in the story, too, that we’ve probably missed. The text displays an awareness of the dangers of foetal alcohol syndrome when the angel warns Samson's mother to eschew liquor during his gestation period. Also, how many people were aware that Samson ruled the Israelites as a Judge for 20 years? The character we encounter in the Bible is not a slightly less hairy cousin of King Kong, but a man of considerable intelligence with a tragically insatiable ego.

The world of the Judges is a place of uncertain borders, shifting alliances, prophets, freaks, despots and dreamers. Samson lives in a terrain that shimmers with the same God-haunted shadows and sense of dread as Flannery O'Connor American South - a land of loyalties and passions that can both inspire holiness and murder.

Samson is the Elvis of the Old Testament; the icon who loves his God and his country, shocks and enthrals both his friends and enemies, and yet slides into the jump-suit and drugs phase of decrepitude while living in a mansion called "Graceland".

The Hebrews of Samson's time could identify well with the blacks of the segregated South. In Samson’s time the Philistines people ruled the Hebrews with not so much an iron hand as one arrayed with jewels. The idea of being able to fight against a people of comparatively stratospheric technology and taste seems absurd. One would have to be crazy to try and match them in repartee, never mind combat.

At such a time, perhaps, a crazy person is who’s needed.

When the angel of the Lord appears to Samson’s mother, he doesn't make any promises that her son with establish a fair and just society, or even that he will one day have a comfortable pension fund. No, he gives her a prophecy that is ominous in its brevity.

He "shall begin to" rout the Philistines from the land. Those three words sum up the raison d'être of her son's existence in space and time. And so the shadows already begin to edge across the page.

Christian readers may be remembering John the Baptist - another man with a glorious assignment, who fulfilled his mission with honours yet ended his life in the company of a drunken king and a girl called Salome. The story of Samson doesn't shy away from this messy struggle between the earthy profane and the terrifying brilliance of the sacred. The angel who visits Samson's mother doesn't easily fit into either category.

Samson’s father immediately seeks to find a name for this mysterious figure. He wants to "get a handle" on the uncanny. The relationship between Manoah and his wife is perhaps the most neglected element of the narrative. It is tender, sometimes funny, and sad. The way they deal with the perplexities of an encounter with the spiritual contrasts with other stories of extraordinary births (Joseph & Mary, Samuel's parents....). The most beautiful comparison the author draws, though, is with a deeper, more ancient record: Adam & Eve.

When the angel reappears, Samson's mother is alone in a field. Here we have an inversion of Eve's encounter with the Serpent. This time, the angel, the voice of God speaks truth and not lies. The angel is doing his job, acting as a servant of God and 4 not, as the Serpent did, as a rival. The results of the Fall are evident in the locale that the message is delivered. She is standing in a field. Fields were invented with the advent of agriculture, the taming of nature. Rather than evil coming into a verdant garden, the beauty of truth steps into a harsh and oppressed universe.

The duty falls upon the mother to convince her husband that the angel is in the field. Her trusting husband doesn't assume that his wife is delusional but drops whatever he's doing and runs, as Peter did to the tomb, to where the mysterious messenger is standing. There is something of the divine about him. He uses the phrase "I am" in response to a question, and Manoah grows more curious, and more desperate to identify him. Perhaps smiling at their bewilderment, the angel replies with a sensational flair for the enigmatic, "Why do you ask my name, seeing it is

Wonderful?"

The obsession with finding a name - a signifier - for the incredible parallels Adam's naming of the animals. But Manoah's actions also mirror those that Peter will take a thousand-odd years later. He suggests that they take advantage of the meeting, settle down and barbecue a lamb. The angel applauds the gesture but suggests they offer a sacrifice to God instead. Manoah agrees, and his obedience leads to a spectacular encounter with the bona fide no-other-way-to-explain-it supernatural.

Boom! The angel soars to heaven in the flames. With the visceral judgement of a skilled film director, the writer lingers in the scene to show the beautiful response of the two human beings. Manoah is in a panic as his synapses crackle with unearthly information.

”We're going to die,” he assumes, probably waving both hands in the air. His wife is the balm on his furrowed brow, displaying the quality of their relationship and her intellect. Using logic, she eliminates that possibility and takes him home. Normal life returns.

Samson's infatuation with the non-Hebrew girl is a puzzle. The event distresses his parents (who have undoubtedly looked up at the sky every day for the past couple of decade for any sign of their angelic acquaintance). We are told, though, that they "did not know that it was from the Lord". Did God inspire an unrighteous relationship? Are we to disregard any moral choices, bad or otherwise that Samson appears to take? Did he have any free will in the execution of his outrages? This is a problem that recurs through Scripture, from the hardening of the Pharoah's heart to the giving over of Judas to darkness. If there is an easy answer to this paradox, I haven't found it.

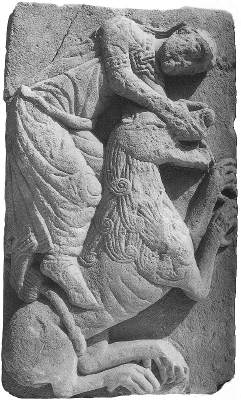

Samson’s subsequent encounter with "the young lion" is the stuff of Sunday School Crayola fests. The roaring prince of the beasts could also serve as a mirror of Samson himself. Interestingly, it is the Holy Spirit that empowers Samson to slay his pponent, and not his agility or physique. In fact, although Samson wanders through Amalekite land (the race of giants spawned by the mysterious Nephlimn) there is no mention of him having a gargantuan frame. For all we know, which isn't very much, regular everyday Samson may have been Clark Kent to warrior Samson's Superman.

In this early display of strength, there are already seeds of trouble planted in the prose. Why is Samson wandering around alien-occupied vineyards? As a Nazarite forbidden to sip alcohol, this is akin to Trappist monk hanging out at a karaoke contest?

Perhaps the lion's attack was a warning? Something sent to make him jump? Alas, all it seems to give our hero (and he is a hero, a perfect example of an Aristotelian flawed warrior; complete with crucial weakness, Achilles-style) a powerful taste for danger. Samson enjoys returning to this place of all good things. Though he can't taste the wine of this promised land, surely he can enjoy the honey? The Edenic imagery returns when Samson brings back a motherlode of honey to his parents. This is a decidedly non-Kosher variety, seized from a hive found in the decayed carcass of the long-since-slain lion. Eve's giving Adam forbidden fruit has been used to justify male chauvinism for aeons; here, Samson, the apotheosis of the macho-aesthetic, repeats the act.

Samson's flirtation with the forbidden betrays an arrogance and a lack of respect for anyone's life. His wedding-day becomes an opportunity to humiliate his in-laws with a riddle that, if solved, would also reveal to his parents precisely where that honey came from. Faced with bankruptcy due to exorbitant nature of the wager that Samson has raised, his new-relations coax the solution to the riddle out of Samson's new-wife. Outraged when he discovers she has saved her family from financial ruin, Samson publicly compares her to a heifer and storms off. His best man is left in one of the most awkward situations since records began and accepts Mrs Samson as his wife. To pay off the bet and restore his hammered ego, Samson kills 30 men and plunders their possessions. His pride is further assaulted at the discovery of his companion's marriage to his wife.

The subsequent orgy of violence features the lynching of both the young girl and her father by their peers. It's an awful hurricane of destruction that shatters the lives of everyone in its path. During its terrible reign over the vicinity, an exhausted Samson does mutter something about a desire "to quit" (v.9) but his pride propels him deeper into his killing spree.

His personal vendettas drag him into the realm of the political. His own countrymen bind him and hand him over to the Philistines. Very few people in history truly appreciate violent revolutionaries who claim to represent their interests. That's why it was such a surprise when the Jews chose Barabbas over Jesus when Pilate offered them either prisoner. Though Samson is guilty of a multitude of transgressions, it is at this point in the narrative that his miserable, wanton, life gains a new significance.

That the ropes binding Samson are broken and that he kills the recently jeering Philistines is no surprise. Note, though, that it is not Samson's innate strength that is credited with breaking the bonds that held him. Rather, the text implies that they disintegrated. His release is thus a supernatural event; as miraculous as the splitting of the earth and the revealing of a spring that quenches the thirst of the battle-weary Samson.

God's blessing is evidently on Samson. The warrior now rules the land for 20 years. There is no mention of violence. Peace, it appears, has arrived. Such are the perfect conditions for legends to form.

The hill where the Philistines were butchered is named after the jaw- bone of the ass that Samson used as his weapon. In this era of prosperity and fame, Samson discovers political power. At such glorious heights, the oxygen seems to thin, and Samson begins to buy into his own mythology. The fall comes swift. A prostitute is scarcely a rare sight on the streets of Gaza, nor does such a woman represent a personal conquest for a man of Samson's prestige. But he sees her and lust takes its rapid course.

The people of Gaza have not grown as lackadaisical as Samson. They know the legends that have circulated for two decades, and are only too aware of his presence in their town. The fact that he is with one of their woman presents them with an opportunity to neutralise a human weapon of mass destruction.

Samson shrugs off the shame of fornication by tearing off the giant city gates and carrying them off. The town is humiliated but alert. Samson is unhurt but his ego – like the gates – is now unhinged.

The final act of Samson's life is as great a part of popular mythology as his reputation was in his own day. It's also just as confused. The story of Samson and Delilah is a reproduction of his parent's relationship, except all that was golden in the older couple's lives is replaced with the desperate and the decayed. To portray Samson as a lustful hedonist is to reduce him to a caricature and to do an injustice to the story. The writer wants to return to the idea of trust.

All that follows is an exploration of this most fragile aspect of love, carried out in one of the most violent of the Bible's stories. Samson loved Delilah. Delilah is not the prostitute he seizes in the heat of a Palestine afternoon, nor the trophy wife he throws aside in the name of pride. Yes, she is a Philistine, but, no, she is not a pathological temptress.

Eden's imagery blows back into the text as she, herself, is tempted. The Philistine grandees ply her with offers of cash for the man she is wedded to. The passage echoes, of course, the twisting of Judas from a disciple to traitor. It is a record of the corrupting power of greed, but the subsequent sequence of events documents the complexities of human relationships. Samson awakes bound in bow-strings and ropes. Surely he realises his wife must have been involved in these attempts on his life?

Had he abandoned his Nazarite vows and got drunk when she asked him to identify his sole weakness while he is rolling in a merry stupor? Perhaps not. More probably, Samson is so possessed with love for Delilah that he practices negative hallucination and refuses to acknowledge the nefarious mechanics at work in the world around him.

For Delilah, the text suggests that money is no longer the impetus for her quest for her husband's weakness. His lies are humiliating her in the eyes of her peers, and also proving that he does not trust her. She has the affection of the Bible's most famous warrior - a man whom, we are told, will fall asleep in her lap - but she does not have his trust.

The pain that this brings to her stems from the fact that it proves he will not surrender his pride, his ego, his identity to her. In such relationships, a partner can urge the other to humiliate themselves as proof of their love: To say, "I will make myself nothing" for you.

Martin Scorsese's film "Life Lessons" features an ageing but esteemed artist whose young Muse threatens to abandon him and his self-importance unless he kisses a policeman. Delilah has captured the heart of Samson. Will he surrender his very life to her?

Samson's "soul was vexed to death" by her tear-soaked demands that she tell him the secret of his strength. Perhaps with his head between his mighty hands, he tells her that he is powerless if his seven great locks are shorn from his head.

Seven locks. The traditional picture of Samson is of a wild-haired man whose mane is as tangled as his personality. But here the writer gives us a new picture. A figure emerges who has the regal dignity of Bob Marley.

We look back at Samson as Delilah strokes these locks, the most famous hair in the world. At a Sikh Temple I once visited a beautifully engaging woman told us human strength is found in the hair. She stroked her own as a gesture and said, "Remember

Samson."

But maybe we've got it all wrong. There's no explicit evidence in the text that Samson’s power as found in what grew out of his skull. Throughout his life, it was the Holy Spirit that flared through his body and God surrounded his days on Earth with the miraculous. Why did he never cut his hair? Because he was a Nazarite.

Samson didn't choose this ascetic lifestyle. It may have been a hunger for self-determination that led him to commit his excesses. But, as a ruler of the Hebrews for 20 years, he kept his long hair as a sign of his calling. In letting his wife arrange for a man to come and shave his head, he was finally letting go of God and naming her as the sovereign of his life.

The text describes Samson's strength leaving him as she tormented him, not when the razor cut across his scalp. Previously, Samson was a sinner who had been given the privilege of a relationship with a God of justice and mercy. But now, "the LORD had left him". Once Samson had enjoyed fame for destroying Philistine food by tying foxes together and setting their tails on fire in a field of corn. Now Samson is forced to do an animal's chore. He performs an ox's job of working a mill; transforming corn he would have once destroyed into bread for the glitterati of a civilisation once again dominant in the land.

The situation is as ludicrous as Saddam Hussein working as a Kuwaiti pipe-line polisher. Here, though, Samson is blind. His eyes are gouged out; all is darkness except his memories. What does he think as the images of his great and terrible life splinter through his mind? The women. The murders. The thefts. Does he pray for forgiveness?

Traditionally, the Samson who stands with his arms outstretched between two pillars is a repentant one. When he pushes at these supports, a rooftop on which 3,000 Philistines are revelling comes crashing down on the banqueters beneath. Has a noble and repentant hero made the ultimate sacrifice? The Bible suggests that Samson was driven primarily driven by revenge. He prays that at least one of his eyes may be avenged, and in the following act of destruction Philistine cultural and political domination is shattered. The angel's prophecy has been proved correct. Samson's life has led to the beginning of the ending of their age. Hope is found in these final verses, despite the death of each and every actor. Samson's hair may have grown back, but he doesn't trust in this physical feature for any strength. Instead, he asks God for a miracle.

It is this faith that enables him to answer the calling to which he was born. Like Job, his sufferings have led him to call on the name of the LORD. But more beautiful than this final submission is the hope that the Christian reader finds in this most visceral of episodes. Samson stands in the same pose as we picture a man nailed to a tree. The death of Jesus also heralded the end to one kingdom. But now, in the midst of rubble and rainbows, we can rejoice in the one which is here and yet also to come.

Samson, Delilah, Christianity, Theology

5 Comments:

I'm curious as to why after Monoah had prayed to God for the Angel to appear again and give directions on how to raise the child that the Angel appears again to Monoah's wife and not to Monoah himself. If Monoah was the one looking for the direction why would God send the angel to Monoah's wife?

Also, does Monoah's wife have a name?

His wife is never named in the Scriptures, neither is Samson's wife or the prostitute. The first woman named is Delilah.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

HOPE is a radically different quality to optimism.

The thousands of voices you can hear in the pages of the Bible are rarely optimistic. When we read their stories we can see why. In Scripture we find little evidence to put our faith in human nature.

When Jesus tells his disciples to love their enemies this is a revolutionary act. It is unnatural, confounding every impulse and precedent. The Old Testament documents the human striving for vengeance and power. From the story of Cain and Abel onwards we witness the curdling jealously which churns through relationships.

The history of Israel provides few grounds for optimism. It teaches us that kings so close to God they can write psalms and proverbs are fallen men who can stoop to murder. In the tales of the judges we see heroes such as Gideon and Samson ensnared by weakness.

On this evidence, have no reason to be optimistic that the followers of Jesus will be able to obey his teachings and live a life defined by love. The first two millennia of church history is sobering proof of our failure to honour Christ’s thirst for justice.

It is easy to condemn the knights who fought in crusades or the officials who founded the Inquisition or the priests who would not give men and women the Bible in their own language, but we have no reason to think we will do any better in our generation.

We live in the wealthiest percentile of Christendom while millions of fellow believers are in nations wracked by poverty. A tenth of Christians live in danger of persecution. If these men, women and children were members of our flesh and blood family, would we sit back and watch them die on a news report? Wouldn’t we empty our bank accounts to rescue them from hunger and pain? As citizens in the most affluent democracies in history we are participants in a scandal.

Christianity is not a faith for wishful-thinkers, who expect people to eventually do the right thing. At the heart of Jesus’ message is a call for repentance, not just reform. To be baptised in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit is to admit that nothing in our bank accounts, no framed certificates on our wall, no passport in our pocket, and no New Year’s Resolution can save us from the lurking power of sin. Jesus did not not teach his disciples to pray: “Take note of my achievements.” Instead, he told them to say: “Forgive us our trespasses.”

This is not a faith which shies from the reality of evil and the depravity of humanity. It confronts the horror. The call to repentance is the sound of a great hope breaking into history. It is God’s diagnosis of the sickness that has poisoned his creation and his declaration that the healing power of the Holy Spirit is now at work in his world.

We do not like to be told we are sinners. We prefer to rejoice as part of a wonderful creation, marvelling at the design of our bodies, the delights of love and the work of our engineers and artists. When we look at the beauty of nature, we feel fortunate to be part of this pageant. We are primed to praise our creator. Surely this is enough?

Throughout history, the church has lulled itself into thinking that it is on the verge of utopia. If only the right Prime Minister or President could be elected, righteousness will bubble up... When we start having thoughts like this we know we are infected with optimism.

The European church in the early 20th century was enthralled by the concept of progress and the perfectibility of the human person. It started looking at the violent and spectacular pages of the Old Testament not as a document of the savagery of man and the persistent love of a living creator, but as a metaphor for our deepest longings.

The catastrophic consequences of a culture which is not alert to its capacity to sin are scattered across the history of the last 100 years. Modern and supposedly rational man laid train tracks which led to extermination camps. Just when humanity was allegedly reaching its zenith, we as a species indulged in sin more primitive and evil than any Philistine outrage.

There are still survivors of Auschwitz alive today. They know what happens when a supposedly Christian civilisation forgets to reverently worship its creator and begins to dabble in nationalism and indulge in pride. In previous centuries, Europe and America invented theological justifications for the slave trade and treated men and women made in the image of God as commodities.

This track record of transgression would crush all hope if forgiveness was not the pulse which beats at the heart of reality. Incredibly, so the Bible tells us, it is not the filth and pulverising power of sin which will have the final victory. Instead, God will redeem his creation.

In the image of the cross we see his sacrificial commitment to this goal. God is not separate from his creation but sharing in its suffering. In the resurrected Jesus, God brings man not only into his presence, but into himself. He is not ashamed to call a man baptised in the Jordan his son, and this man is not ashamed to call his disciples brothers.

The mystery and love we see here is more wonderful than our own history is terrible. This is the core of the cosmos, the creator’s call to his creatures to embrace his joy. Yes, the act of repenting involves turning from our sin, but it means we can look up at this glorious healing light.

Paul told the Christians in Rome: “For we know the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves who have the first-fruits of the spirit groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we are saved.”

Now, in the first years of the 21st century, the task of the people who make up the church is to witness to this hope in every way we can. How can we best do this? A good start might be to read the prophets who kept hope alive during some of the darkest epochs.

Micah had wise words: “He has showed you, O man, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly, and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

HOPE is a radically different quality to optimism.

The thousands of voices you can hear in the pages of the Bible are rarely optimistic. When we read their stories we can see why. In Scripture we find little evidence to put our faith in human nature.

When Jesus tells his disciples to love their enemies this is a revolutionary act. It is unnatural, confounding every impulse and precedent. The Old Testament documents the human striving for vengeance and power. From the story of Cain and Abel onwards we witness the curdling jealously which churns through relationships.

The history of Israel provides few grounds for optimism. It teaches us that kings so close to God they can write psalms and proverbs are fallen men who can stoop to murder. In the tales of the judges we see heroes such as Gideon and Samson ensnared by weakness.

On this evidence, have no reason to be optimistic that the followers of Jesus will be able to obey his teachings and live a life defined by love. The first two millennia of church history is sobering proof of our failure to honour Christ’s thirst for justice.

It is easy to condemn the knights who fought in crusades or the officials who founded the Inquisition or the priests who would not give men and women the Bible in their own language, but we have no reason to think we will do any better in our generation.

We live in the wealthiest percentile of Christendom while millions of fellow believers are in nations wracked by poverty. A tenth of Christians live in danger of persecution. If these men, women and children were members of our flesh and blood family, would we sit back and watch them die on a news report? Wouldn’t we empty our bank accounts to rescue them from hunger and pain? As citizens in the most affluent democracies in history we are participants in a scandal.

Christianity is not a faith for wishful-thinkers, who expect people to eventually do the right thing. At the heart of Jesus’ message is a call for repentance, not just reform. To be baptised in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit is to admit that nothing in our bank accounts, no framed certificates on our wall, no passport in our pocket, and no New Year’s Resolution can save us from the lurking power of sin. Jesus did not not teach his disciples to pray: “Take note of my achievements.” Instead, he told them to say: “Forgive us our trespasses.”

This is not a faith which shies from the reality of evil and the depravity of humanity. It confronts the horror. The call to repentance is the sound of a great hope breaking into history. It is God’s diagnosis of the sickness that has poisoned his creation and his declaration that the healing power of the Holy Spirit is now at work in his world.

We do not like to be told we are sinners. We prefer to rejoice as part of a wonderful creation, marvelling at the design of our bodies, the delights of love and the work of our engineers and artists. When we look at the beauty of nature, we feel fortunate to be part of this pageant. We are primed to praise our creator. Surely this is enough?

Throughout history, the church has lulled itself into thinking that it is on the verge of utopia. If only the right Prime Minister or President could be elected, righteousness will bubble up... When we start having thoughts like this we know we are infected with optimism.

The European church in the early 20th century was enthralled by the concept of progress and the perfectibility of the human person. It started looking at the violent and spectacular pages of the Old Testament not as a document of the savagery of man and the persistent love of a living creator, but as a metaphor for our deepest longings.

The catastrophic consequences of a culture which is not alert to its capacity to sin are scattered across the history of the last 100 years. Modern and supposedly rational man laid train tracks which led to extermination camps. Just when humanity was allegedly reaching its zenith, we as a species indulged in sin more primitive and evil than any Philistine outrage.

There are still survivors of Auschwitz alive today. They know what happens when a supposedly Christian civilisation forgets to reverently worship its creator and begins to dabble in nationalism and indulge in pride. In previous centuries, Europe and America invented theological justifications for the slave trade and treated men and women made in the image of God as commodities.

This track record of transgression would crush all hope if forgiveness was not the pulse which beats at the heart of reality. Incredibly, so the Bible tells us, it is not the filth and pulverising power of sin which will have the final victory. Instead, God will redeem his creation.

In the image of the cross we see his sacrificial commitment to this goal. God is not separate from his creation but sharing in its suffering. In the resurrected Jesus, God brings man not only into his presence, but into himself. He is not ashamed to call a man baptised in the Jordan his son, and this man is not ashamed to call his disciples brothers.

The mystery and love we see here is more wonderful than our own history is terrible. This is the core of the cosmos, the creator’s call to his creatures to embrace his joy. Yes, the act of repenting involves turning from our sin, but it means we can look up at this glorious healing light.

Paul told the Christians in Rome: “For we know the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves who have the first-fruits of the spirit groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. For in this hope we are saved.”

Now, in the first years of the 21st century, the task of the people who make up the church is to witness to this hope in every way we can. How can we best do this? A good start might be to read the prophets who kept hope alive during some of the darkest epochs.

Micah had wise words: “He has showed you, O man, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly, and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

Post a Comment

<< Home