A Plea for Hope Humanity When Talking About Heaven and Hell

Please do send me your ideas and insights. Thanks!

Christians have urged people to repent of their sins and avoid the fires of hell in the 20 centuries since Jesus preached his message on earth. We have responded to humanity’s fear of death by affirming that, yes, there is great reason to be afraid of dying – unless people ask Jesus to forgive their sins eternal punishment in hell awaits.

Throughout human history, religions have focused on the afterlife and the promise of happiness for those who do good deeds and the assurance of punishment for those who commit evil. The Christian message alters this paradigm with the introduction of grace. It is not because of a Christian’s own good works that he or she will be welcomed into heaven, but because the death of Jesus in our place means that every sin can be forgiven. Similarly, the teaching that there is no one who has not sinned means that everyone is destined for eternal punishment if they do not repent.

This coupling of a universal crisis with a global opportunity for salvation has spurred the greatest missionary effort in history. If the threat of an eternity in hell looms over everyone, then no task in a Christian’s lifetime could be more urgent than telling everyone you know how to escape the coming horror. The greatness of God’s grace means that this message should be preached to anyone – whether a pre-school child or a prisoner on Death Row.

The presentation of a straight choice between an eternity in heaven or hell is highly effective. Who wouldn’t want to go to heaven? The prospect of heaven makes hardships in this life more tolerable and the presence of hell appeals to our sense of justice. It seems fitting that murderous dictators who escape punishment in this life will receive fitting judgement in the next.

The choice between entry into heaven or hell is the “sales pitch” potential Christians are given and it defines the theology of converts who then seek to persuade their children, family, friends and colleagues to make a similar decision.

Suggesting that we need to think carefully and prayerfully about our conceptions of heaven and hell can feel unsettling and downright dangerous. Rethinking seems synonymous with “casting doubt” and why would anyone want to downplay either the hope of heaven or the threat of hell? Similarly, who would want to risk unthreading an evangelical message which has proven so effective in growing the church?

There are good reasons to be suspicious of anyone wishing to sow doubt about doctrine. People familiar with the story of Genesis will remember the serpent’s fateful question to Eve which began with the words “Did God really say…?”

Nevertheless, as people who love the Bible and seek to love God with our hearts, souls and minds, we must check in every generation that the message we proclaim is the same message Jesus revealed. In the 2,000 years since Jesus lived among us, hair-raising heresies have attacked his church like computer viruses and deluded good men and women. Thankfully, in every century brave reformers have followed the example of Christ and stepped to scrape the layers of false religion off the gospel truth.

Evangelicals have spent much of the last 200 years fighting to preserve doctrines such as Biblical inerrancy, the Virgin Birth and substitutionary atonement from the attacks of sceptics. Such people with a passion for orthodoxy and a zeal to defend truth should not be painted as opponents of change and reform. They have a track record of changing the world.

Catholics and Protestants alike can now salute the courage of the Anabaptist martyrs who defied the teachings of the established church and baptised adults. Evangelicals in the 19th century were compelled to oppose slavery, even though the wealthiest Christian nations in the world profited from the trade and their opponents had their own Bible verses to justify the practice. And in the 20th century early Pentecostals reintroduced the world to charismatic gifts which mainstream churches thought had ceased.

Churches, traditions and families who have struggled for generations to protect the primacy of the Bible now have a duty to sit down and read it, study it and share its treasures with the world. This should lead us into a deeper appreciation of God’s action in history, the work of the risen Jesus, and the mission and hope to which we are called. It is inevitable that this process of exploration, excavation and reformation will involve a fresh investigation of our teachings about the afterlife.

The Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans and the Vikings had precise models of how humans can escape punishment in the next life. Their models of the universe had a heaven above and a hell below. Today, competing world religions offer systematic theologies which promise to deal with our fear of death, our hope of paradise, and our desire that evil will be punished.

It is fascinating that neither the writers of the Hebrew scriptures, nor the authors of the Gospels, nor the Apostles in their epistles presented a crystal clear picture of the afterlife. We were not given flow-charts of the kind which adorn Egyptian tombs. This hasn’t stopped us trying to provide the clear instructions provided by other faiths. The danger is that by presenting the church and its message as a GPS system which will help you reach heaven we are offering people a different gospel to the one Jesus gave us. We are diluting his radical promise of reconciliation and redemption if we condense his proclamation into a series of steps to get an entry ticket into heaven or a pass to avoid hell.

Furthermore, if our human instincts and cultural traditions have led us to “Christianise” an essentially pagan paradigm of the afterlife, we miss out on learning the fantastic truths the Bible can teach us about life and death.

The pursuit of a truthful understanding of God’s revelation should compel us to examine existing doctrines, but there are also pragmatic and moral reasons for digging deeper. The medieval paintings of countless people being cast into chambers of incineration now have an awful counterpart in the extermination camps of the Holocaust, the killing fields of Cambodia and the scenes of genocide in Rwanda. With extraordinary glibness, the church often presents an image of the afterlife in which all people who have not made a conscious, personal choice to follow Jesus are destined to be locked in such suffering for eternity. Does the Bible teach that God has ordained relentless pain and endless misery for so many of His creatures? Christians who are serious about their faith, who live in a world haunted by the horrors of Auschwitz and the dread of nuclear war must ask if this is the true message of Jesus. If we have not humbly wrestled with this question we have no reason to expect a suffering world to take us seriously.

Similarly, in the affluent West the idea of heaven as an escape from the uncertainty, poverty and sickness of daily life has lost much of its power. Traditionally, faiths project visions of paradise which match their founders’ ideas of utopia but a superficial presentation of a future of material wealth and general bliss is no longer compelling. This is what advertisements promise on every page of a glossy magazine. The Bible has wonderful things to say about heaven but a shallow portrayal of this realm as a zone of unique consumer fulfilment will persuade few to accept the challenge and sacrifice of following Jesus.

In this essay I am certainly not proposing to offer a definitive account of what we should think about death, heaven and hell, but I am making the plea that we do think about death, heaven and hell. In highlighting what the Bible does say on these subjects, it is my hope that the Holy Spirit will deepen the roots of beliefs that need to be strengthened and uproot any which should be abandoned. A reassessment of our teachings on these subjects may prompt us to change the way we evangelise, but we should not fear reforms if they result in a fuller and truer presentation of the good news of Jesus Christ.

WHAT DID JESUS HAVE TO SAY ABOUT HELL?

When Jesus spoke of “hell”, he most frequently used a word which referred to a definite place, Gehenna. This was the Valley of the Son of Hinnom and it divided Jerusalem from the hills to the south and west and marked the boundary between the land of Judah and Benjamin. We should not immediately assume when Jesus talks about Gehenna he is also referring to our concept of an eternal realm of punishment which features in so many world religions.

Gehenna was notorious as a site of sin, paganism and destruction on the edge of God’s holy city. In the Hebrew scriptures it represented the horror of demonic idolatry. We see this in Jeremiah 7:30-31:

“The people of Judah have done what is wrong in my eyes says the Lord. They set up their loathsome idols in the house which bears my name and so defiled it; they have built shrines of Topheth in the valley of Ben-hinnon, at which to burn their sons and daughters. That was no command of mine; indeed, it never entered my mind.”

In this instance, the valley is the location of the sacrificial murder of children and God makes it clear that such a concept should be utter anathema. The valley is the scene of a crime of godless destruction in a promised land.

God’s servant, King Josiah, dealt with this abomination in 2 Kings 23:10:

“[Josiah] desecrated Topheth in the valley of Ben-hinnon, so that no-one might make his son or daughter pass through the fire for Molech.”

In these passages, a location outside Jerusalem is the scene of fiery and barbaric acts by the enemies of God. In the writings of the prophet Isaiah, such a location, again on the outskirts of the holy city, becomes a burning place where such enemies are themselves destroyed. We read in Isaiah 66:24:

“As they go out they will see the corpses of those who rebelled against me, where the devouring worm never dies and the fire is not quenched.”

Jesus takes this imagery of the incineration of sin and uses it in his own teachings. But instead of seeing alien “enemies” as the targets of destruction, he calls on his audience to purge themselves of sin. In Mark 9:43, we read:

“If your hand causes your downfall, cut if off; it is better for you to enter into life maimed than to keep both hands and go to hell, to the unquenchable fire.”

In Mark 9:47, he continues:

“And if your eye causes your downfall, tear it out; it is better to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to keep both eyes and be thrown into hell, where the devouring worm never dies and the fire is never quenched.”

This is an explicit allusion to Isaiah 66:24 and the idea of a place outside the holy city where God’s enemies are destroyed. Jesus was equating his kingdom with this righteous city and telling his audience that if they persisted in individual sin they would be counted as God’s enemies.

If Jesus’ audience were people who hungered for the transformation of Jerusalem into the city Isaiah envisaged and longed for its release from Roman occupation and a return of righteousness, this message would have shocked them to the bone. Yes, Jesus appeared to imply, the kingdom is coming but unless you deal with everyday sin you will not be able to enter its gates; it is your own behaviour, not that of some external enemy, which must be conquered.

Jesus’ brother, James, picked up this theme in his epistle, linking the forces of destruction represented by hell to the human compulsion to sin. He wrote in James 3:6:

“And the tongue is a fire, representing in our body the whole wicked world. It pollutes our whole being, it sets the whole course of our existence alight and its flames are being fed by hell.”

Just as the fires of infant sacrifices were a sign of human sin at its most heinous in the days of Jeremiah, so the violence of spoken words were an offence and a scandal in God’s creation. This is an echo of Jesus’ remark in Matthew 5:22 that “whoever calls [a brother] ‘fool’ deserves hellfire”.

Scholars have suggested that in Jesus’ day Gehenna was also the location of a smouldering and sulphurous rubbish dump on the edge of the city. The image of hell as somewhere ruined goods were abandoned chimes with Jesus’ words in Matthew 23:13-15:

He states: “Alas for you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! You shut the door of the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces… You travel over land and sea to win one convert; and when you have succeeded you make twice as fit for hell as you are yourselves.”

In Luke 12:4-5, Jesus does link the idea of hell as a destination for the souls of people who have opposed God’s reign on earth. In this case, he is impressing on his audience the authority and power of God and contrasting this with the temporary, fleeting might of persecuting authorities.

He said: “To you who are my friends I say: Do not fear those who kill the body and after that have nothing more they can do. I will show you whom to fear: fear him who, after he has killed, has authority to cast into hell. Believe me, he is the one to fear.”

But before we draw the conclusion from these verses that Jesus is speaking of hell as a timeless prison cell, we see in Matthew’s account once again the idea of hell as the place of annihilation, where evil is vanquished for good.

We read: “Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Fear him rather who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.”

If both the soul and the body are destroyed it is clear than a person ceases to exist in any form. When Jesus speaks of Gehenna he does so to assert God’s sovereignty over all life and to revive Isaiah’s vision of a holy city where God’s people dwell once he has conquered and destroyed sin. His message is that sin can be destroyed, that it will not be tolerated for eternity, and that his followers should make bold efforts to purge their own lives of sinful behaviour – no matter how insignificant these vices may seem. In taming how they use their hands and eyes they are preparing to be citizens of God’s kingdom.

The Palestine in which Jesus lived and taught was abuzz with different theories and doctrines about the afterlife, the resurrection and the destiny of history. Jesus did not make any of the statements we have just read in a vacuum and there is much work to be done in coming to understand how each would have been interpreted by his audience. If historians and theologians can help us gain new insights into Jesus’ understanding of Gehenna and the parallel realm of Hades, which we shall touch on in a moment, the church will owe them a debt of gratitude.

Some traditions within Judaism have seen Gehenna as a purgatorial place where people are purified for “the world to come” but Jesus’ description of it as a place of destruction appears to reject this teaching. As we wrestle with this subject matter it is clear how keenly we as a church need to learn about the Judaism of Jesus’ time because our superficial understanding limits our appreciation of his gospel teaching. There is a great sense in which we are making up for lost time.

We were not helped when the translators of the fourth century Latin Vulgate decided to render realms such as Sheol and Gehenna as “infernus”. Thirteen centuries later, the writers of the King James Version used the word “hell” on each occasion. By now our imaginations were full of apocalyptic images and ideas about Dante’s inferno. Thus, the complexity of the Jewish worldview was shrouded and the English-speaking world ended up using a word which may have its roots in Norse realm of the dead. It is a tragic irony if we have kept alive a linguistic memory of the Vikings’ Hel, the female ruler of a shadowy terrain, but have forgotten the riches of the faith Jesus knew so intimately.

It would be especially helpful to know more about how Jesus interacted with the Greek ideas that had swept into Palestine. The religious and political elite were thoroughly Hellenised (yet another reason why fishermen and carpenters from Galilee were regarded as hicks). When we read Jesus’ account of Lazarus in Hades, is this merely Sheol by a Greek name? If so, what had happened in the centuries since Job and Samuel so that this sleepy and shadowy zone had become perceived as a place of great canyons separating the suffering bad and the happy good?

Alternatively, was Jesus taking the concept of the Greek underworld that would have been intensely familiar to his audience and using it in a parable to expose their hypocrisies and unwillingness to repent? The apostle Peter, writing in his second epistle, borrows directly from Greek mythology when he makes the Bible’s only reference to Tartarus, a place even deeper than Hades. He writes in 2 Peter 2:4 that “God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into hell [Tartarus] and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgement”. This does not suggest that Judeo-Christian theology was directly shaped by the Greek story of how both the Cyclopes and Cronos the Titan were imprisoned in Tartarus, but it shows that the church was ready to engage with existing concepts to communicate wider truths.

THE DESTRUCTION OF EVIL

The image of evil destroyed once and for all recurs throughout the Hebrew scriptures and the New Testament. It emphasises the power of God to cleanse His creation and contrasts with ideas of a hell teeming with sinners who will suffer for eternity.

The expectation of God’s victory is powerfully expressed in Malachi 4:13:

“The day comes, burning like a furnace; all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble, and that day when it comes will set them ablaze, leaving them neither root nor branch says the Lord of hosts.”

The apostle Peter also takes forward this idea of a purging of a polluted creation that will rid the cosmos of evil for good. He writes in 2 Peter 3:7:

“By God’s word the present heavens and earth are being reserved for burning; they are being kept until the day of judgement when the godless will be destroyed.”

The Apostle Paul appears to anticipate eternal life as a unique God-given gift. This new life is described as an alternative to death – not as a way of escaping a celestial torture chamber.

He writes in Romans 6:23: “For sin pays a wage, and the wage is death, but God gives freely, and His gift is eternal life in union with Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Attempts can be made to argue that by “death” he actually means an everlasting experience of torment but why would Paul write in so deliberately confusing a manner about a matter of eternal consequence?

The image of “eternal fire” in Jude 1:7 is directly linked to a moment in human history when men and women were killed stone dead:

“Remember Sodom and Gomorrah and the neighbouring towns; like the angels, they committed fornication and indulged in unnatural lusts; and in eternal fire they paid the penalty, a warning for all.”

This suggests that we do not have to think of condemnation to eternal fire as synonymous with eternal suffering. The idea is deeply rooted in church culture, however, and has excited the imaginations of many preachers.

The Puritan Calvinist churchman Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) wrote: “The body will be full of torment as full as it can hold, and every part of it shall be full of torment. They shall be in extreme pain, every joint of ’em, every nerve shall be full of inexpressible torment. They shall be tormented even to their fingers’ ends.”

Such extra-Biblical pronouncements on the specific experiences of individuals in the afterlife have directed the thinking of generations of people about the afterlife. Because we are by nature fascinated with this subject, congregations have demanded to know more than the Bible tells us and preachers have been happy to oblige.

The image of a moment of purging - a doing-away-with of sin once and for all - through a final death continues in Revelation 20:13-15:

“The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and Death and Hades gave up the dead in their keeping. Everyone was judged on the record of their deeds. Then Death and Hades were flung into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death; into it were flung any whose names were not to be found in the book of life.”

In this picture death itself is dead. So where in the Bible do we gain the idea of endless suffering? The starkest passage suggesting this is found a few chapters earlier in the same book, Revelation, but applies to a very specific group of people – those who worship the “beast”. At this stage in the Revelation, the author, John, is using a rich mixture of apocalyptic language to describe the indescribable. He mentions the 144,000 who are destined for salvation, and the symbolic writing is a blend of the prophetic and the poetic which should not be read in isolation from the rest of the Revelation – much less the rest of the Bible.

He writes in Revelation 14:9-11:

“A third angel followed, saying in a loud voice, ‘Whoever worships the beast and its image and receives its mark on his forehead or hand, he too shall drink the wine of God’s anger, poured undiluted into the cup of his wrath. He shall be tormented in sulphurous flames in the sight of the holy angels and the sight of the holy angels and the lamb. The smoke of their torment will rise forever; there will be no respite day or night for those who worship the beast and its image, or for anyone who receives the mark of its name.”

Perhaps intentionally, the picture of torment here is a parallel with the horrors of Gehenna, where children were sacrificed to a pagan god. The reference to the forehead and hand could be an allusion to God’s instruction to His people to wear His commandments on these parts of the body; just as child sacrifice was the antithesis of what God wanted, the false religion personified by the beast was an inversion of God’s laws of righteousness and now God’s wrath will forever pulverise its power. Whether we regard this passage as a spectacular metaphor for God’s conquering of evil or as a description of the fate which awaits specific people who follow the figure represented by the beast in a future age, it cannot be right to see this passage as the template for what will happen to non-Christians when they die.

We should remember that the realms of eternity are not governed by the rules of space and time we experience as humans on a small planet orbiting a star. PS Johnston, writing in the New Dictionary of Biblical Theology (2000), comments:

“[We] now know that space and time are relative, even in the present universe, that time is experienced differently at different velocities, and that visibility is affected by gravity. DC Spanner suggests intriguingly that one recently discovered feature of the universe may be illustrative of hell. A spaceship travelling into a black hole would be sucked in and annihilated. Yet an observer would continue to see the ship appear to hover above the horizon of visibility, gradually fading but without definite end. Similarly, hell might be experienced as annihilation but observed as continuing punishment, gradually fading from view.”

WHAT DOES HAPPEN WHEN WE DIE?

Is there evidence of people “going to hell” or “going to heaven” at the moment of death? The Bible does not give us a straight answer, and – remarkably – the Jewish people lived with apparent uncertainty about the afterlife. Their relationship with God did not begin with a decision to follow Him because in return He would reward them with eternal life. Rather, God chose them as His people in an expression of His free, sovereign will. He made a covenant with Abraham and resolved to bless the world through this man’s descendants. Regardless of whether they were in exile or in Jerusalem, they were His people.

Though they could not comprehend why He loved them or where He was taking them – or where they would go after death – His faithfulness defined their reality. As Christians and as people of God at this time in history, we would do well to learn from the faith of these righteous people who may have lacked a precise scriptural description of the afterlife but who were seized by the hope which comes from knowing a loving God.

Job did not expect to enter heaven upon the moment of his death. Rather, he anticipated entry into Sheol, the abode of the dead. Sheol refers both to the grave and the “pit”.

We read in Job 17:13-16:

“If I measure Sheol for my house,

If I spread my couch in the darkness,

If I call the grave my father

And the worm my mother or my sister

Where, then, will my hope be.

And who will take account of my piety?

I cannot taken them with me down to Sheol,

Nor shall we descend together to the dust.”

Such pessimism is also seen in Isaiah 38:18, when King Hezekiah declared upon his recovery from illness:

“Sheol cannot confess you

Death cannot praise you,

Nor can those who go down to the abyss

Hope for your truth.”

Jonah described his experience in the belly of a fish as being in Sheol. He said in Jonah 2:2:

“I called out to the Lord, out of my distress,

And he answered me;

Out of the belly of Sheol I cried,

And you heard my voice.”

The early Hebrew scriptures do give a hint of an afterlife. In 1 Samuel 28 King Saul visits the medium of En-dor when he wants to speak to the deceased prophet Samuel. At first she sees “a god coming up out of the earth” and then Samuel asks: “Why have you disturbed me by bringing me up?”

This suggests that the afterlife was conceived as a place of deep rest. In Numbers 20:24, when the moment comes for Aaron to die it is described as the time for him to be “gathered to his people”.

A shaft of light scorched away some of the mystery surrounding the afterlife during the exile in Babylon. Daniel glimpsed a future in which God’s power would eclipse the might of earthly rulers and establish His authority over all time in a moment of extraordinary justice.

In Daniel 12:2 we read:

“But at that time your people will be delivered,

Everyone whose name is entered in the book:

Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake,

Some to everlasting life

And some to the reproach of eternal abhorrence.”

This passage anticipates resurrection as a moment of resuscitation and reawakening. But in the New Testament there are hints of a conscious existence between death and resurrection.

The most notable is in Luke 16, Jesus’ story – often considered a parable but not specifically identified as one – of a rich man and poverty-struck Lazarus, who gathered crumbs from his table. The poor man dies and is carried by angels to the “bosom of Abraham”. When the rich man dies he goes to Hades – not Gehenna – which is a place of thirsting from which he can look up and see Lazarus standing “far off” with Abraham. He then pleads that an angel will be dispatched to warn his brothers of the fate which awaits them. In this story the rich man, Lazarus and Abraham all appear to be in the same realm, but a “great chasm” divides the men.

This may be a precise description of the pre-judgement afterlife (Jesus did raise Mary and Martha’s brother, also called Lazarus, from the dead; however the description of the mourning party at his home makes it very unlikely that he was the poor man described by Jesus) but the idea that conversations can be held between those who are punished and those who are honoured appears nowhere else in the Bible. The story is sandwiched between teachings on divorce and temptations so it is reasonable to assume its primary purpose is to communicate an ethical lesson. As such, it gives a graphic warning of the implications of ignoring the poor and failing to recognise the dignity of a righteous man who enjoyed no rewards in this life.

We are likely to continue to puzzle over how we should think about Hades, a realm we are told will be destroyed when it is thrown into the “lake of fire” mentioned in Revelation 20:24. In the meantime, we should take away from this tale the lesson that all people are individuals of eternal consequence who will continue to exist when the material world and its fleeting wealth have vanished.

The conversation between Jesus and the thief during the agony of the crucifixion has been studied for hints about the afterlife.

In Luke 23:43 we read: “And he said, ‘Jesus, remember me when you come to your throne.’ Jesus answered, ‘Truly I tell you: today you will be with me in paradise.’”

This beautiful exchange took place as Jesus was nailed on a cross beneath the sign “King of the Jews”. Mockers taunted Jesus as he suffered but it is clear from the wider story that this comment was not another instance of cruel sarcasm. The thief recognised he was dying beside a remarkable man, and his statement can be read as an expression of respect and solidarity.

Jesus’ own disciples and the religious experts had failed to grasp the eternal nature of his kingdom so it is unlikely that the thief expected to approach Christ’s throne in heaven. The promise that he would be with him “in paradise” is enigmatic, and it has been used to argue that believers are instantly in heaven upon their death.

The phrase “paradise” appears rarely in the Bible, but a popular idea around the time of Jesus was that a garden for the righteous existed; there was even a notion that Eden had been preserved unstained by sin. Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians 12:2-4:

“I know a Christian man who 14 years ago (whether in the body or out of the body, I do not know – God knows) was caught up as far as the third heaven. And I know that this same man (whether in the body or apart from the body I do not know – God knows) was caught up into paradise, and heard words so secret human lips may not repeat them.”

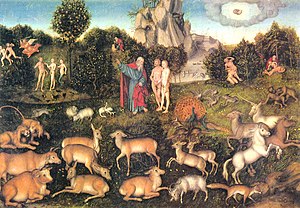

This idea of a multi-chambered heaven is fascinating, and the concept of a garden where God’s people await the fulfilment of history is appealing. Certainly, Paul looked forward to being with his Lord when he died and – especially when taken together with the Lazarus story – it is clear that Christians do not have to fear abandonment upon death. God has revealed enough since the time of Job to assure us that His love extends upon the grave. The idea of a restored Garden of Eden chimes with the Bible’s recurring theme of God working to restore and reconcile His people to one another and to himself. Isaiah looked forward to the day when the “wolf will live with the lamb” and we read in Revelation 2:7:

“You have ears, so hear what the Spirit says to the churches! To those who are victorious I will give the right to eat from the tree of life that stands in the garden of God.”

One day we will meet the thief and we ask him what happened in the moments after he breathed his last. I wonder, though, if Jesus’ promise was not a gesture towards the afterlife but a description of the awesome significance of these final hours of their lives on earth.

Eden was where the creator breathed life into Adam, forming the first man out of dust, and where the two walked together as friends. Amid the shame and horror of Golgotha, the thief had an intimacy with the author of life that will stand out from the perspective of eternity as one of the greatest honours a human could know. This man who had lived a wretched life had the insight to recognise Jesus as someone exceptional and he suffered alongside him. As Jesus took his final breath God’s victory over sin was accomplished. In this moment of salvation Christ expressed his kinship with humanity and fellowship of Eden was restored. In a very real sense, as he hang beside his saviour that day the thief was in paradise.

We should be wary of attempting to come up with a concrete system to identify anyone’s eternal destination by linking together the diverse verses we have read so far. However, it is clear that sin is a matter of the gravest importance and the consequences of rebellion against God are terrible. We should stand in awe at the utter victory of God as He annihilates the power of evil. Revelation shows us the cosmic fulfilment of the victory that Christ, the lamb, achieved on the cross. The picture of destruction illustrates the fate from which we were rescued by Christ. We are left in no doubt that God takes sin so seriously that He also cares about our individual behaviour. Our deeds, both good and bad, are registered in eternity.

LET’S TALK ABOUT HEAVEN

Asking Christians to revisit their conceptions of hell should in no way diminish our awareness of the gravity of sin or the might of God’s justice. In fact, it should spur us to worship with new conviction, amazed that we can stand in His presence.

Equally, thinking about heaven should trigger a new appreciation of the wonder of Christ’s work. Heaven is not a never-ending holiday in a bejewelled resort. Rather, it is a vision of what it means to live – now and in the future - in a new relationship with a saviour who loves us, died for us, and now reigns over the cosmos.

Heaven is not a reality divorced from the material world. In fact, by exploring the idea of heaven we come to understand just how intimately the risen Christ is involved with his creation today. In Acts 2:33 we are told:

“Exalted at God’s right hand he received from the Father the promised Holy Spirit, and all that you now see and hear flows from him.”

The martyr Stephen glimpsed the source of the Spirit moments before he was stoned to death. We read in Acts 7:55:

“But Stephen, filled with the Holy Spirit, and gazing intently up to heaven, saw the glory of God and Jesus standing at God’s right hand.”

The greatest reason for excitement about heaven is the prospect of a new stage in our relationship with Christ. The hope of such fellowship was a source of inspiration to Jesus in the hours before his trial and death, and it should also charge our lives with joy.

In John 17:24, moments before Jesus led his disciples to the garden where he was betrayed, he prayed:

“Father, I desire that they also, whom you have given me, may be with me, where I am, to see my glory that you have given me because you loved me before the foundation of the world.”

What awaits us is a fuller revelation of Jesus and the full revealing of whom he has made us. When we encounter Christ we will fully comprehend the power and love which has sustained us all our lives. This meeting will be the culmination of a process of coming to know Jesus which has unfolded throughout the journey of the human life. As we fix our eyes on him, as we welcome into our lives and are consumed by his life, so we will also discover our true identity.

As we are told in Colossians 3:1:

“Were you not raised to life with Christ? Then aspire to the realm above, where Christ is, seated at God’s righted hand, and fix your thoughts on that higher realm, not on this earthly life. You died, and now your life lies hidden with Christ in God. When Christ, who is our life, is revealed, then you too will be revealed with him in glory.”

God’s people will not escape the judgement that Daniel saw in his visions as a captive in Babylon or John glimpsed while on the prison island of Patmos, the Guantanamo Bay of Roman rule. But the judgement will be a moment of wonder when we become aware of the work Christ has performed in our lives.

CS Lewis wrote in his essay The Weight of Glory (1949):

“It is written that we shall ‘stand before’ Him, shall appear, shall be inspected. The promise of glory is the promise, almost incredible and only possible by the work of Christ, that some of us, that any of us who really chooses, shall actually survive that examination, shall find approval, shall please God. To please God... to be a real ingredient in the divine happiness... to be loved by God, not merely pitied, but delighted in as an artist delights in his work or a father in a son – it seems impossible, a weight or burden of glory which our thoughts can hardly sustain. But so it is.”

Arrival in the presence of Christ is not like checking in at a five-star hotel. It is more like the moment of metamorphis when a caterpillar wakes up with wings.

It says in Philippians 3:19-20:

“He will transfigure our humble bodies, and give them a form like that of his own glorious body, by the power which enables him to make all things subject to himself.”

And again, in 1 Corinthians 15:49 we are promised:

“As we have worn the likeness of the man made of dust, so we shall wear the likeness of the heavenly man.”

HOW WIDE A HOPE?

How many of us can hope to experience this transformation? Will righteous people who lived before Christ share in this wonder? Is it limited to people who believed and were baptised? What about men and women who faithfully followed other religions or none but responded to their God carved conscience by living a life of love, mercy and compassion?

Is it too much to hope that the many passages which mention destruction refer to the incineration of sinful identities and not the complete annihilation of individuals? Is there a Biblical case for suggesting that a person could experience destruction and regeneration?

If you search the text with a torch for a hint that this might be possible you will find at least one faint sparkle.

We have already looked at 2 Peter 3:7, which reads:

“By God’s word the present heavens and earth are being reserved for burning; they are being kept until the day of judgement when the godless will be destroyed.”

However, in Paul’s letter to the Romans, he suggests that the God’s plan is good news for all creation – not just humans. He states in Romans 8:19-23:

“For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption of sons, the redemption of our bodies.”

If the message of the Bible is big enough to hold in tension Peter’s prophesy of the earth’s destruction and Paul’s promise of the release and liberation of creation, perhaps the Gospel is good news both for the thief on the cross who turned to Jesus with respect and the other who was too locked in his sin to recognise his saviour? Just as Christians live in the hope of receiving a new identity when their sinful nature will be scorched away, might even the most wretched scoundrel yet discover that on the other side of death what awaits is Christ-bought redemption?

At this moment in church history, advancing universalism, the idea that everyone will have an eternal place in God’s kingdom, involves explaining away so many difficult warnings and prophecies that the argument quickly sounds like an exercise in wishful thinking. In all Bible study we must submit our own preferences and inclinations to the sovereignty of God and the authority of scripture while retaining the deepest respect for the teachings passed down by the Spirit-filled church.

Similarly, many (most?) Christians who cherish the Bible also reject the idea of conditional mortality or annihilationism. There are many variations of this theory but in essence it suggests that eternal life is a gift of God without which we would by nature perish. The passages which speak about the destruction of sinners mean exactly that – they will not inherit eternal life and they will simply cease to exist. This does not mean that they will escape judgement at the mass resurrection of the dead but it suggests that a final extinguishing of existence awaits.

Revelation 20:13-15, which we read earlier, could be interpreted as pointing to such an event:

“And the sea gave up the dead who were in it, Death and Hades gave up the dead who were in them, and they were judged, each one of them, according to what they had done. Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire. And if anyone’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire.”

Bruce Milne, in the evangelical classic Know the Truth (1982), rejects the concept of conditional mortality with an appeal to logic and a sense of justice.

He writes:

“Sinners will receive the just deserts of their sin. Annihilation would prevent this, since one can hardly speak of divine justice if a person passes away to oblivion after a life of gross self-indulgence and evil. Does it square with the biblical witness to the justice of God that a Hitler will never be called to render account for his enormous wickedness, or, if he is called to account, his judgement consists merely of passing into oblivion?”

This is a compelling argument and justice is at the core of God’s identity. But we must remember that we are saved because of an act of love by God which defies the laws of human reason. Christians are sinners who are spared the “just deserts” of their sin. The forgiveness of sins won by the death of Christ is rightly described as scandalous and made the minds of Jews and Greeks boggle (1 Corinthians 1:22-25).

And while few theologians would want to argue in front of an audience that Hitler, Stalin or Osama bin Laden could escape the full blast of God’s wrath, it would be much less difficult to find men and women willing to make the case that Christ’s saving power can reach into the masses of people who will never have a definite conversion experience in their decades alive on earth. Logic may spur us to call for the punishment of criminals but it can also make us cry out for mercy to be shown to others. Conservative Christians will make the case for the salvation of children who die in infancy, the mentally disabled, and people who have never heard the proclamation of Jesus’ call to repentance.

We may also feel the demand for mercy bubbling within us when we think of people who strive to lead righteous lives while following other faiths or none. Is a humanist who simply cannot conceive of the existence of the supernatural but who nevertheless devotes his or her life to loving neighbours someone who is in rebellion against God and deserving of condemnation? Can people who only encountered Christianity in its most belligerent or insipid or superstitious form and were rightly horrified be said to have rejected the gospel? Are they destined to either perish in a moment of destruction which will eclipse the atomic horror of Hiroshima a million-fold or, failing that, spend forever in the howling darkness of an afterlife untouched by grace?

The evangelical legend John Stott found himself in a cauldron of controversy in 1988 when he suggested that the good news of Jesus is not, on the last day, bad news for the majority of people who have ever lived. In Essentials, a dialogue with a liberal theologian, he wrote:

“I have never been able to conjure up (as some great Evangelical missionaries have) the appalling vision of the millions who are not only perishing but will inevitably perish. On the other hand… I am not and cannot be a universalist. Between these two poles I cherish the hope that the majority of the human race will be saved. And I have a solid biblical basis for this belief.”

This is rightly controversial territory because nothing less than eternal life and death are at stake. Those who put forward the hope of great salvation do not do so because they believe we are creatures who deserve eternal life – Romans 3:23 tells us that “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God”. Rather, they place their hope in the character of God. Genesis, the first book of the Bible, records a scene in which God has resolved to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah. Abraham pleads for mercy with the creator of the universe and God agrees to spare the city if just 10 righteous people are found there.

If God would respond with mercy to the pleas of a flawed patriarch such as Abraham, how much more hope is there for humanity now that the risen Christ is enthroned at his Father’s right hand? The epistle to the Hebrews may be addressed to believers, but surely all people can draw comfort from the verses in 4:14-16:

“Since then we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast our confession. For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathise with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin. Let us then with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need.”

On judgement day, if we had the audacity to complain that some sinners were either allowed to enter the new kingdom or were spared eternal suffering, we could be rebuked with a quick reference to Jesus’ parable of the labourers in the vineyard in Matthew 20:1-16. It’s a beautiful story so let’s read it in its entirety:

“For the kingdom of heaven is like a master of a house who went out early in the morning to hire labourers for his vineyard. After agreeing with the labourers for a denarius a day, he sent them into his vineyard. And going out about the third hour he saw others standing idle in the marketplace, and to them he said, ‘You go into the vineyard too, and whatever is right I will give you.' So they went. Going out again about the sixth hour and the ninth hour, he did the same. And about the eleventh hour he went out and found others standing. And he said to them, ‘Why do you stand here idle all day?’ They said to him, ‘Because no one has hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You go into the vineyard too.’ And when evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his foreman, ‘Call the labourers and pay them their wages, beginning with the last, up to the first.’ And when those hired about the eleventh hour came, each of them received a denarius. Now when those hired first came, they thought they would receive more, but each of them also received a denarius. And on receiving it they grumbled at the master of the house, saying, ‘These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.’ But he replied to one of them, ‘Friend, I am doing you no wrong. Did you not agree with me for a denarius? Take what belongs to you and go. I choose to give to this last worker as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or do you begrudge my generosity?’ So the last will be first, and the first last.”

It is the worst type of exegetical jiggery-pokery to take a passage of Jesus’ teaching on the kingdom and interpret it as a straight description of post-death experiences; such practices do an injustice to the text. But at the very least the precedent and principle of God possessing a capacity for wild generosity that defies our concept of justice is established here.

Jesus is the ultimate expression of God’s nature and in his teaching and life he condemns every shade of sin but shows a mercy to individuals which exposes the pride and hypocrisy lurking behind stultifying religious legalism. In John 8:2-11 the scribes and Pharisees try to trap Jesus by hauling a woman caught in adultery before Jesus. They want to stone her and secure evidence to charge Jesus with heresy. The story is familiar but let’s encounter once again the Jesus we have talked about so much in this essay. We read in verses 7-11:

“And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, ‘Let him who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.’ And once more he bent down and wrote on the ground. But when they heard it, they went away one by one, beginning with the older ones, and Jesus was left alone with the the woman standing before him. Jesus stood up and said to her, ‘Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?’ She said, ‘No one, Lord.’ And Jesus said, ‘Neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no more.’

Jesus does nothing to condone the sin of adultery. Not even the most wild-minded theo-libertine would try and use this passage to argue that infidelity is justified. But we see a way of dealing with sin which contrasts with the human instinct to seek a punishment to fit the crime. Jesus knew that shortly he would bear a punishment for our sins that would unleash a grace capable of forgiving centuries of crimes.

Am I arguing that the church should embrace universalism? No. Such a revolution would require far greater scriptural proof than this essay provides. Do I think congregations should now accept annihilationism? No. That is not the purpose of this essay. I am the layest of laymen, I am ignorant of Hebrew and Greek, and I am the beneficiary of a Christian tradition that has been shaped by both the joy of heaven and a knowledge of the utter tragedy of a death without the hope of eternal life.

But I do think that our understanding of the afterlife has been shaped by images and ideas in our culture to a far greater degree than we might have recognised. Our vision of the cosmos might owe as much to essentially pagan conceptions of paradise and hell than it does to Paul’s description of a creation in the process of rebirth and a people who are being transformed through brotherhood with Christ.

If we explore the rich complexities of the Bible’s teachings on the afterlife, I do believe we will find reason to hope that the all-sufficiency of Christ’s atoning death is a work of such wonder and power that the reach of God’s grace is certainly greater than we might dare imagine. The deeper we go on this journey through God’s word, the clearer we see the face of His son who loved us and gave himself for us. It is when we are confronted with Mary’s son that the doors of hope seem to swing widest.

We are told in Hebrews 2:9:

“What we do see is Jesus, who for a short while was made subordinate to the angels, crowned now with glory and honour because he suffered death, so that, by God’s gracious will, he should experience death for all mankind.”

And in 1 John 2:2: we read:

“He is himself a sacrifice to atone for our sins, and not ours only but the sins of the whole world.”

Jesus himself declared in John 12:31-32, shortly before he went to the cross:

“Now is the hour for judgement for this world; now shall the prince of the world be driven out. And when I am lifted up from the earth I will draw everyone to myself.”

The miracle of the cross had cosmic consequences which go far beyond the salvation of humanity. We discover in Colossians 1:19-20:

“For in him God in all His fullness chose to dwell, and through him to reconcile all things to himself, making peace through the shedding of his blood on the cross – all things, whether on earth or in heaven.”

CONCLUSION

This short survey of Biblical texts concerning the afterlife shows, I hope, that the model of hell as an eternal concentration camp is rooted in our culture but not in scripture. We can speak with certainty of judgement and the destruction of the forces of sin, but only with the greatest humility should we attempt to describe the process by which God will accomplish His plans; grave caution should be exercised in any discussion of the eternal destination of any people. We see through a glass darkly (1 Corinthians 13:12); however, we can see Jesus (Hebrews 2:9), so let us fix our eyes in the author of our faith and seek to act justly, show love, and pray for mercy.

We should cease to talk about heaven as the perfect retirement destination but instead delight in the hope of knowing Jesus who is enthroned there and whose Spirit lives in our hearts, transforming us into Christ’s likeness.

We may find that our evangelistic models need to be reformed to better reflect the wonder of the Christ-won joy to which we are called and the generosity of the love which has been lavished upon us. Will such changes diminish the church’s passion for the gospel or the urgency of the mission? Not at all! Rather, in nurturing a more Biblical faith, there is cause for greater excitement. We have the spectacular honour of being entrusted with God’s “ministry of reconciliation” (2 Corinthians 5:19) and there is much work to do in the service of a sinless, utterly just and all-conquering God. As Paul said in Ephesians 1:9-10:

“He has made known to us His secret purpose, in accordance with the plan he determined in Christ, to be put into effect when the time was ripe – namely, that the universe, everything in heaven and on earth, might be brought into a unity in Christ.”